"A Feminist Legacy" About menu item on womenschoralsociety.org

“Strong in Song Since 1934”: The Legacy of the Eugene Women’s Choral Society

As posted on Medium (click link to visit online)

Open/download/print a PDF version

By Hannah Steuer • Follow on Medium • 16 min. read • Dec. 11, 2025

Photo credit: Bill Johnson via Women’s Choral Society

Founded in 1934 as the Women’s Choral Club, the organization now known as the Women’s Choral Society (WCS) is the oldest “all-women’s” choir in the state of Oregon. Over the past 92 years, WCS has maintained a significant public role in Eugene’s musical community through its concert programming, student scholarships, and music-making opportunities for treble singers. However, there is little scholarship on how WCS’s founding patrons and subsequent leaders sustained the ensemble’s longevity amid a range of societal pressures and continuing systemic misogyny. By examining the ensemble’s development, my research illustrates how the Women’s Choral Society has consistently challenged cultural expectations and limitations placed on musical women. In doing so, this project underscores the impacts of “all-women’s” ensembles on their members, their leaders, and the communities they serve.

This article is divided into 5 sections: Origins and early days; Maud Densmore, the “Guiding Light” of WCS; Literature review — Music clubs and women’s access to the arts; A stage of their own; Continuing the legacy — Advocacy and social justice in the 21st century.

A note on terminology: Throughout this article I utilize ensemble names interchangeably. The organization adopted the title “Women’s Choral Society” in 1970, so I use “Women’s Choral Club” when discussing pre-1970 history.

Additionally, I use quotation marks when writing about WCS as an “all-women’s” group. This editorial choice reflects the understanding that trans/gender-nonconforming individuals have existed in the margins throughout history, and may very well have been a part of this ensemble despite lack of documentation. In recent years, the organization has made a deliberate shift to identifying as a “treble” choir in their continued commitment towards inclusivity.

Origins and early days

The Women’s Choral Society celebrates over 90 years of involvement in the Eugene music scene. A look into their past reveals how the strong foundations of this ensemble set them up for success for years to come.

The Women’s Choral Society¹

In 1934, the University of Oregon’s chapter of the musical sorority Mu Phi Epsilon sponsored a series of music courses and lectures for their members. As a result of these gatherings, the patronesses of Mu Phi Epsilon decided to create an all-women’s choir for the larger community. The story goes²:

“Mrs. W.E. Robertson one day approached Miss Maud Densmore asking whether she would ‘foster a project she had in mind.’ She was told that would depend ‘if it were something really worthwhile and having a future.’ Mrs. Robertson’s suggestion was that this was the time to organize a women’s chorus in Eugene where she felt there was much talent and to let Mr. [John Stark] Evans use the group to illustrate his lectures…A notice in the paper asking women interested to respond brought in more than 300 applications, of whom 110 were finally accepted.” — Women’s Choral Society website

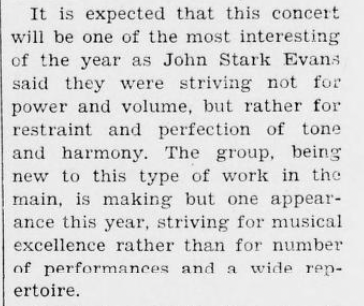

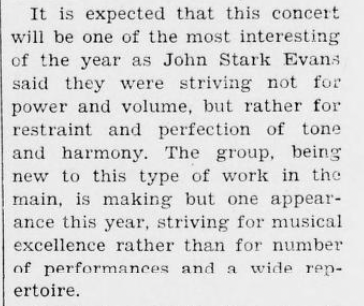

Thus the Woman’s Choral Club was born, with John Stark Evans at the podium and Maud Densmore as Chairman and accompanist. An accomplished local organist, professor, and conductor of the Eugene Gleemen, John Stark Evans already was well-known and celebrated in the community. Although Evans’ role as director of the Women’s Choral Club was brief, as illness forced him to step away from the group after less than 2 years, he was still much credited for the initial success of the ensemble. In anticipation of the Women’s Choral Club’s very first performance on April 18, 1935, the below advertisement appeared in the Oregon Daily Emerald:

Oregon Daily Emerald (Eugene, OR), 1935³

After Evans’ departure, the group was led for one year by local musician Frances DeLoe, who was succeeded by director Cora Moore Frey for five years, and then by Glen Griffith for the next six. Each conductor brought with them a different approach to programming repertoire, collaborating with local charities, and advertising the group. Membership changed dramatically throughout the course of these first 15 years, and the ensemble ranged in size between 86 and 110 singers.

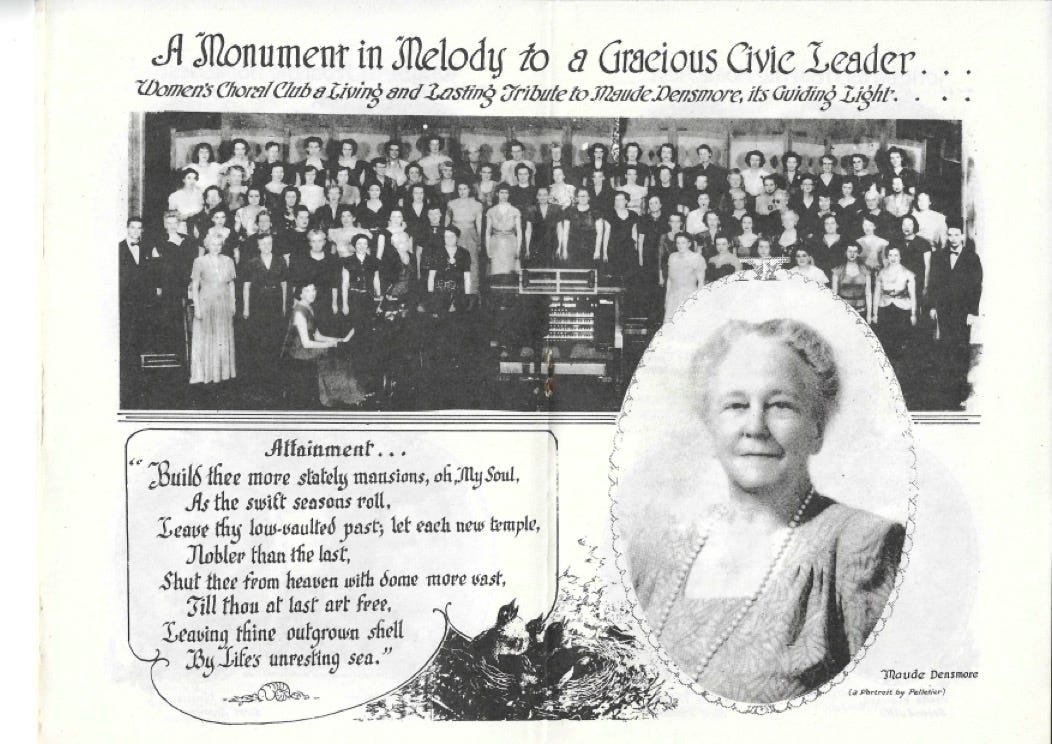

Despite having several different conductors, a variety of accompanists, and numerous shifts in personnel, the Women’s Choral Club only grew in strength during this time, earning regular public praise for their performances and charitable pursuits. The source of this success was unanimously agreed upon, as one woman remained at the helm for 16 years with unmatched dedication: Maud Densmore.

Maud Densmore, the “Guiding Light” of WCS

Maud Densmore was born in 1876 in Stanton, Nebraska⁵. As a young adult, she graduated from the Creighton Conservatory of Music in Omaha before moving with her family to Eugene, OR in 1895. Upon her arrival, she began establishing herself as a fixture of the Eugene musical community: teaching music, playing piano for local social clubs, and singing as an Alto in various collegiate choruses. In 1905 she married local apparel merchant Alton Hampton, with whom she lived for the next 15 years. Maud joined the honorary music sorority Mu Phi Epsilon in 1915, and quickly became an invaluable member to the chapter. 1922 was a difficult year for the couple: Alton Hampton went bankrupt, and Maud completed her petition for divorce, citing “cruel and inhuman treatment.” Maud moved into her own house, and soon after began running a successful women’s apparel business of her own. The pair had no children.

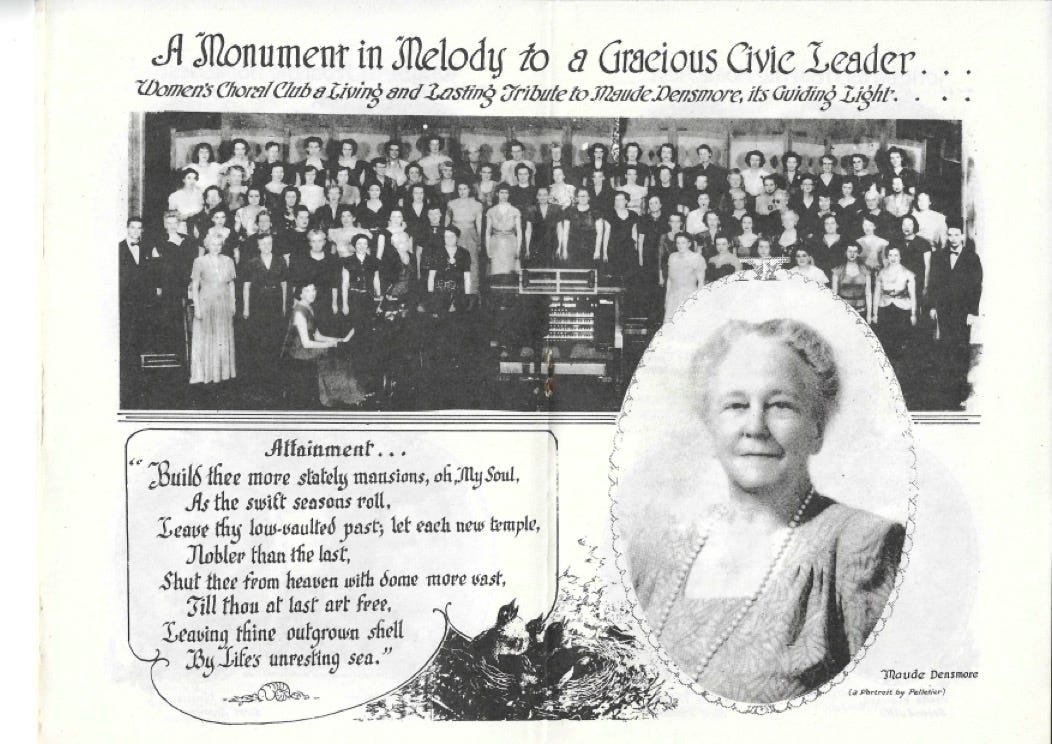

The Home (Eugene, OR), 1952⁶

Densmore was largely responsible for the creation of the Women’s Choral Club, for which she patroned with other members of the Mu Phi Epsilon music sorority, served as the first accompanist, and chaired for years to come. As the group developed artistically, Densmore cultivated the ensemble’s culture among its singers: organizing social events such as banquets and fashion shows, creating seating charts with witty epigrams for each member, collaborating with businesses to obtain sponsorships, and partnering with local organizations for the ensemble’s benefit concerts. Perhaps the most notable feature of Densmore’s legacy is the scholarship project she initiated in 1943, which remains to this day a central priority of the organization⁷.

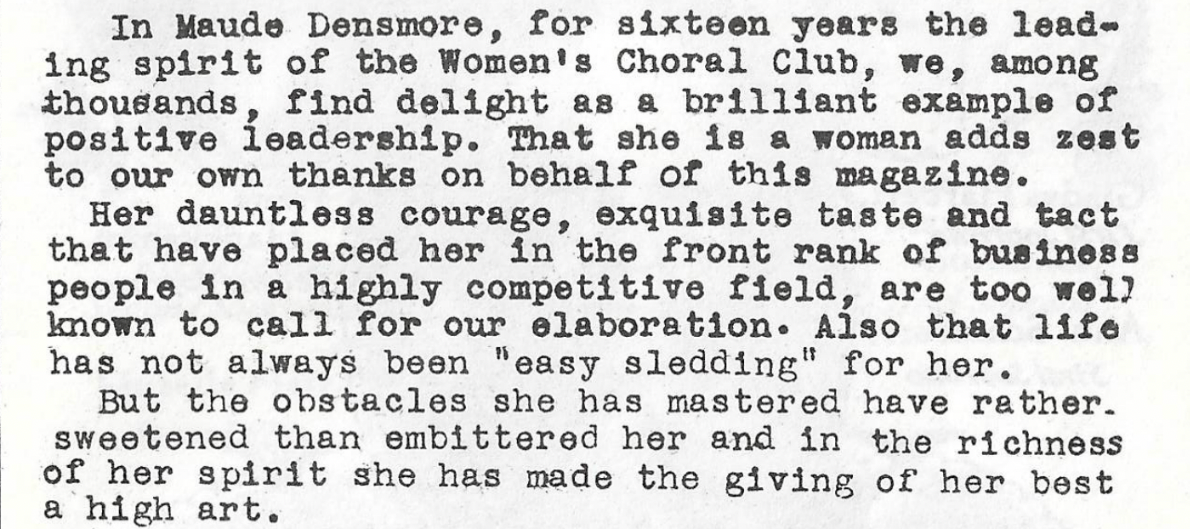

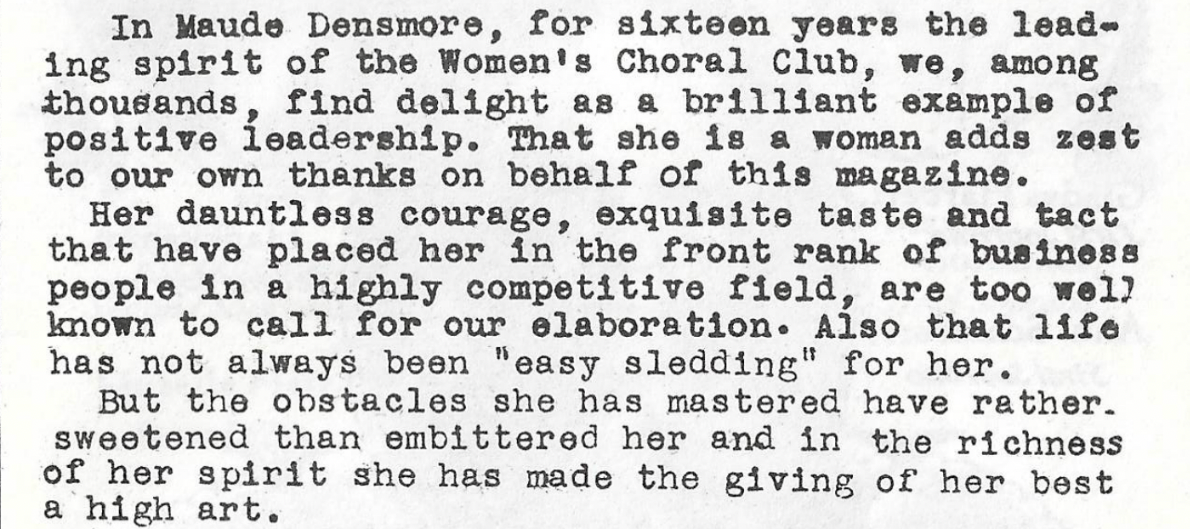

It is difficult to overstate just how loved and appreciated Densmore was, both within the ensemble and in the larger community. Below is an excerpt from “The Home”, an independent local magazine that in 1952 published an entire issue on the Women’s Choral Club.

The Home (Eugene, OR), 1952⁸

Densmore’s community was well aware of her extraordinary accomplishments despite personal (i.e. marital) challenges. As is hinted above, the fact of her womanhood — and therefore gendered assumptions around her ability to be an effective authority figure — made Densmore all the more celebrated by those who valued women’s leadership. Thus, in exploring the impacts of Densmore’s patronage, it becomes essential to consider the feminist implications of her legacy.

It is evident that Densmore’s influence within the Women’s Choral Club went beyond merely the social structure of the group. The excerpt from The Home magazine continues⁹,

“To [Maud Densmore], an accomplished performer, music is at once a prime incentive and reward and, in sensing its universal urge, she has implanted in each of her splendid chorus something of her own philosophy and watched its flowering into into its present nobility and beauty for Eugene’s lasting memory. Surely a melodious monument to and within the life of a great leader.”

Despite her being in an administrative role, Densmore clearly made considerable contributions to the ensemble’s artistic development. Further, her guidance strengthened the interpersonal support among the members, and established avenues for professional success through scholarship funds. The significance of this type of structural support among women was illustrated by musicologist Elizabeth Wood in her 1980 book Women in Music. Wood writes¹⁰,

“Female systems of kin, friendship, and mentorship are crucial not merely for emotional interaction but for formal skill sharing and career shaping…. Courageous older, established women mentors, role models, musical mothers, effective and generous ‘patrons,’ have forced access for women to musical education, maturation, and career options.”

With this framework, it becomes distinctly evident that Densmore’s tenacious, impassioned leadership in the Women’s Choral Club held a deeper meaning: that of resisting gendered limitations on musical women by explicitly empowering their success.

Literature review: Music clubs and women’s access to the arts

In the broader historical context of the ensemble’s formative years under Maud Densmore’s guidance, several prominent and interconnecting societal challenges faced women’s access to the performing arts across the country. The most prominent constraints to groups such as the Women’s Choral Club were based on misogynist notions of women’s obligations to domestic labor, and of their capacity to be musicians with true artistic merit.

Underscoring this cultural landscape in its entirety is systemic racism, as well as racism’s intersection with misogyny to further marginalize women of color. During the era discussed in the subsequent literature (~1900–1950) many racist policies and practices were in affect in Eugene, making access to a group such as the Women’s Choral Club nearly impossible. As such, while there were significant overlaps in the experiences of white women and women of color at the time, the below discussion of the trials and triumphs relating to women’s music clubs is exceedingly (and almost exclusively) in reference to white women. Please see the Notes section for further reading on Black history at University of Oregon, Oregon’s history of racism, and the proliferation of Black clubs in America.¹¹

Eugene Women’s Choral Club rehearsing for their 1961 Winter Concert, under direction of Max Risinger ¹²

Highly influential to situating an analysis of the Women’s Choral Club is the 1997 book Cultivating Music in America : Women Patrons and Activists since 1860, edited by musicologists Ralph Locke and Cyrilla Barr. In Chapter 2, “The ‘Domestic Sphere’? Women and Music in Home,” author Linda Whitesitt discusses the growing popularity of women’s music clubs at the turn of the 20th century. She writes¹³,

“Some men (and women) worried that… involvement in “out-of-home” activities might do damage to home and family. ‘I am persuaded that there are Women’s Clubs whose objects and intents are not truly harmful, but harmful in a way that directly menaces the integrity of our homes,’ the former U.S. president Grover Cleveland was quoted as saying [in 1902]… Fortunately, such worries were not often articulated in print: even the male-dominated musical press trumpeted its praise for the work of women’s clubs.”

The political and social climate in which the Women’s Choral Club originated consequently encompassed a variety of attitudes towards women’s music clubs. After the Second World War, this discourse was at a turning point: while the previous years had drawn women into the workforce in unprecedented ways, giving many new skills and a sense of independence, the postwar era brought a societal push towards the return to female domesticity¹⁴. As such, public perception of women’s music clubs regressed as many women reentered the demanding realm of domestic labor.

Yet women choristers and directors continued to reject the assumption that women’s music clubs were frivolous, unserious pursuits — as attitudes on domesticity shifted, more women in the performing arts began advocating for updated understandings of women musicians. In a 1954 issue of Music Journal, educator Doris Paul recalls a speaker at the convention of the Michigan State Federation of Music Clubs¹⁵,

“The woman who had the floor during a forum for choral directors at [the convention] underlined every word she spoke with emotion: ‘I’m tired of hearing members of women’s choruses in the state referred to in this discussion as “just housewives.” The very inflection used indicates that some people here believe women join music groups only to get away from the grind of baby-tending, cooking, and cleaning. I grant that the girls in my chorus do find singing therapeutic, but the main reason they belong is that they experience an aesthetic pleasure from singing good music; and, as their director, I try to give it to them!’

I had to grip the arms of the chair to keep from jumping up and cheering. I thought of the members of my chorus back home. Some had been music majors in college, and but for the accident of sex that made them women, and consequently homemakers, they would be following music as a profession.”

Further in the article, Paul writes,

“It is an earnest, serious-minded, truly musical group of women, this chorus of mine… I maintain that the women who make up most choruses — mothers’ choruses connected with PTA’s, choruses affliated with women’s clubs, glee clubs made up of nurses or other professional, trade, or industrial groups — join choral organizations because they love to sing and because they enjoy music that presents a challenge. Members are not ‘mere housewives,’ ‘just mothers,’ or a ‘bunch of nurses’ who want to pass their time away singing any old thing the director and the gals happen to know.”

Paul’s article is an insightful rebuke of the dismissive, misogynistic attitudes towards women’s choirs at the time, which assumed that a group of women musicians must somehow be divorced from genuine artistry. This personal account further corroborates the conclusions made in Chapter 2 of Cultivating Music in America, in which Whitesitt writes that “women’s music clubs, by their very nature, challenged this socially accepted notion of woman’s place in the home.”¹⁶ The Women’s Choral Society is situated in this canon — from its inception, the ensemble has opposed societal limitations to their success while adapting to the changing goals of the feminist movement.

Women’s Choral Club ‘Publicity Committee’ works to plan advertising efforts for their upcoming spring concert, Eugene Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), 1956¹⁷

A stage of their own

In 1939, an anonymous author submitted an editorial to a local Eugene newspaper, excerpted below¹⁸:

“In a way our Women’s Choral Club is an expression of ‘women’s rights.” For some years these tuneful ladies have been battling against the inclination to think of them as the ‘Women’s Gleemen” or something of the sort. Just because the Gleemen are older and somewhat more famous is no sign of male monopoly on choral music. The Women’s Choral Club has its place, and its own place, in our community’s musical life.”

The author’s adamant stance is significant in underscoring the fundamental “place” of the Women’s Choral Club and sense of belonging in Eugene. They go on to write, “In their own way the women have built an organization which is different but the adequate counterpart of the Gleemen.”¹⁹ Based on the remainder of the article, it appears that the author likely was not a member of the Choral Club themself, yet they clearly maintained that the ensemble was not “lesser” because it was a women’s group. This sentiment was replicated for many years to come — throughout exploration of the archival documents held by WCS Historian Regina Claypool-Frey, a pattern arises: despite societal disenfranchisement, the ensemble continued to prove its worth in the artistic community for decades.

Early reviews of the Women’s Choral Club may read as slightly condescending, since even praise of the group was based on gendered presumptions of inferiority — as if to say, “What a surprise, women can succeed in music-making?!” For example:

“All in all the comment was, ‘Well, I didn’t know whether to hear a women’s group sing or not, but they certainly did extremely well and I enjoyed the program immensely.” — personal correspondence from Rev. George R. Turney to Maud Densmore, October 26, 1940²⁰

“[The audience] was given ear- and eye-filling proof that ensemble singing by women can be and is exciting musical experience for listener and participant alike, when a well-chosen, well-sung program is presented as was done by the Women’s Choral Club,” — G.E. Gaylord, Eugene Register-Guard, December 1945²¹

These sources offer primary insight into many contemporaneous expectations of women musicians, and further highlight how the Women’s Choral Club began to establish itself as a valued and necessary avenue for the display of women’s genuine musical talents.

•••

As the group continued to thrive into the latter half of the 20th century, there were fewer documented conversations about the implications of being an “all-women’s” group. Increasingly, the broader scholarly conversation on supporting women’s ensembles turned towards repertoire and programming. As discussed by music educators and musicologists such as Doris Paul²², Monica Hubbard²³, and Elizabeth Wood²⁴, the challenges facing directors of “all-women’s” vocal ensembles then became that of finding music of a high enough caliber for adult treble singers.

In 1970, the ensemble officially changed its name to the Women’s Choral Society²⁵. Little documentation is available on the decision to make this shift, raising questions about the impetus for this change: Did “club” have certain connotations that the women wanted to move away from? Was “society” more desirable because of its suggestions of high-status? Were there other administrative considerations?

Additional archival documents from the Women’s Choral Society do offer insight into the changing ensemble culture. For example, early programs often included explicit mentions of “Sisterhood” or shared female identity within the group. By the 1980’s this was less common, as many of the internal messages and external reviews of the group shifted to focusing predominately on their artistry and community service. However, the sentiments of WCS’s members remained poignant. In their 50th Anniversary Concert Program (1984), the Women’s Choral Society described the significance of their group²⁶:

“Since its beginning, the Women’s Choral Society has made three important contributions to the musical life of the community: music of excellent quality and great variety for its concert and outreach programs, financial aid to University of Oregon music students, and a memorable experience for each active member. Special to members of the group is the bond that singing together has created among them — bond of strength, mutual support, and joy.”

This emphasis on community-building within the ensemble suggests that the singers have maintained interpersonal priorities throughout the group’s history. Despite a slight interlude on historical materials surrounding the aforementioned themes, the Women’s Choral Society has only continued to grow in its pursuits of artistry, outreach, and community-building.

Women’s Choral Society Winter concert Program, January 20, 2019²⁷

Continuing the legacy — Advocacy and social justice in the 21st century

Over the past twenty-five years, the Women’s Choral Society has undergone several meaningful transformations. Adopting the motto “Strong in Song since 1934,” the group honors its long history while demonstrating a renewed dedication to empowering its singers. In recent years, WCS has become increasingly engaged with contemporary conversations in music education and social justice advocacy.

In 2017, the choir presented With Liberty and Justice for All, a concert commemorating the centennial of women’s suffrage. Since then, WCS has offered a series of programs that celebrate the power of collective music-making — including We Are the Voices (2019), Rise Up (2020), Let Your Light Shine (2023), Courage Hope Joy (2023), 90 Years of Song and Sisterhood (2024), and Together in Harmony (2024).²⁸

Between 2019 and 2022, the Women’s Choral Society began to reexamine its terminology and membership requirements. The group now welcomes all treble singers, and shares that they are “undergoing a ‘visioning’ process to examine our choir’s identity, mission and commitment to inclusion.”²⁹

Members of the Women’s Choral Society join in song before the start of the People’s March in Eugene, OR. Chris Pietsch / The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), Jan. 18, 2025³⁰

On January 18, 2025, members of the Women’s Choral Society sang together at the Eugene People’s March, part of a national demonstration advocating for reproductive freedom, climate justice, access to healthcare, and LGBTQ+ rights, among other issues. This powerful interaction between music and social justice illustrates just how much our community — and, in turn, the Women’s Choral Society— has evolved in the last ninety years. While the advertisement for their very first concert in 1935 assured readers that the women were “striving not for power and volume, but rather for restraint,” the current members and leadership of the Women’s Choral Society are proud to sing with strength, conviction, and purpose.

Now directed by Dr. Melissa Brunkan, the Women’s Choral Society remains a vital part of Eugene’s musical landscape. Through annual scholarships, collaborations, and performances, the ensemble continues to uphold the commitments on which it was founded. To this extent, WCS is a living tribute to the dedicated efforts of Maud Densmore’s powerful early leadership, alongside the numerous other women who supported in the longevity of the ensemble. The Women’s Choral Society’s legacy is that of service, connection, and enduring resilience, built upon the artistic visions of generations of women; it will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role in the community for years to come.

“A song well sung is always satisfying. But when the curtain falls and the adrenaline diminishes, what sustains WCS is ‘the fellowship and the community among the women,” — Jennifer Smith³¹

•••

“Strong in Song Since 1934”: The Legacy of the Eugene Women’s Choral Society

As posted on Medium (click link to visit online)

Open/download/print a PDF version

By Hannah Steuer • Follow on Medium • 16 min. read • Dec. 11, 2025

Photo credit: Bill Johnson via Women’s Choral Society

Founded in 1934 as the Women’s Choral Club, the organization now known as the Women’s Choral Society (WCS) is the oldest “all-women’s” choir in the state of Oregon. Over the past 92 years, WCS has maintained a significant public role in Eugene’s musical community through its concert programming, student scholarships, and music-making opportunities for treble singers. However, there is little scholarship on how WCS’s founding patrons and subsequent leaders sustained the ensemble’s longevity amid a range of societal pressures and continuing systemic misogyny. By examining the ensemble’s development, my research illustrates how the Women’s Choral Society has consistently challenged cultural expectations and limitations placed on musical women. In doing so, this project underscores the impacts of “all-women’s” ensembles on their members, their leaders, and the communities they serve.

This article is divided into 5 sections: Origins and early days; Maud Densmore, the “Guiding Light” of WCS; Literature review — Music clubs and women’s access to the arts; A stage of their own; Continuing the legacy — Advocacy and social justice in the 21st century.

A note on terminology: Throughout this article I utilize ensemble names interchangeably. The organization adopted the title “Women’s Choral Society” in 1970, so I use “Women’s Choral Club” when discussing pre-1970 history.

Additionally, I use quotation marks when writing about WCS as an “all-women’s” group. This editorial choice reflects the understanding that trans/gender-nonconforming individuals have existed in the margins throughout history, and may very well have been a part of this ensemble despite lack of documentation. In recent years, the organization has made a deliberate shift to identifying as a “treble” choir in their continued commitment towards inclusivity.

Origins and early days

The Women’s Choral Society celebrates over 90 years of involvement in the Eugene music scene. A look into their past reveals how the strong foundations of this ensemble set them up for success for years to come.

The Women’s Choral Society¹

In 1934, the University of Oregon’s chapter of the musical sorority Mu Phi Epsilon sponsored a series of music courses and lectures for their members. As a result of these gatherings, the patronesses of Mu Phi Epsilon decided to create an all-women’s choir for the larger community. The story goes²:

“Mrs. W.E. Robertson one day approached Miss Maud Densmore asking whether she would ‘foster a project she had in mind.’ She was told that would depend ‘if it were something really worthwhile and having a future.’ Mrs. Robertson’s suggestion was that this was the time to organize a women’s chorus in Eugene where she felt there was much talent and to let Mr. [John Stark] Evans use the group to illustrate his lectures…A notice in the paper asking women interested to respond brought in more than 300 applications, of whom 110 were finally accepted.” — Women’s Choral Society website

Thus the Woman’s Choral Club was born, with John Stark Evans at the podium and Maud Densmore as Chairman and accompanist. An accomplished local organist, professor, and conductor of the Eugene Gleemen, John Stark Evans already was well-known and celebrated in the community. Although Evans’ role as director of the Women’s Choral Club was brief, as illness forced him to step away from the group after less than 2 years, he was still much credited for the initial success of the ensemble. In anticipation of the Women’s Choral Club’s very first performance on April 18, 1935, the below advertisement appeared in the Oregon Daily Emerald:

Oregon Daily Emerald (Eugene, OR), 1935³

After Evans’ departure, the group was led for one year by local musician Frances DeLoe, who was succeeded by director Cora Moore Frey for five years, and then by Glen Griffith for the next six. Each conductor brought with them a different approach to programming repertoire, collaborating with local charities, and advertising the group. Membership changed dramatically throughout the course of these first 15 years, and the ensemble ranged in size between 86 and 110 singers.

Despite having several different conductors, a variety of accompanists, and numerous shifts in personnel, the Women’s Choral Club only grew in strength during this time, earning regular public praise for their performances and charitable pursuits. The source of this success was unanimously agreed upon, as one woman remained at the helm for 16 years with unmatched dedication: Maud Densmore.

Maud Densmore, the “Guiding Light” of WCS

Maud Densmore was born in 1876 in Stanton, Nebraska⁵. As a young adult, she graduated from the Creighton Conservatory of Music in Omaha before moving with her family to Eugene, OR in 1895. Upon her arrival, she began establishing herself as a fixture of the Eugene musical community: teaching music, playing piano for local social clubs, and singing as an Alto in various collegiate choruses. In 1905 she married local apparel merchant Alton Hampton, with whom she lived for the next 15 years. Maud joined the honorary music sorority Mu Phi Epsilon in 1915, and quickly became an invaluable member to the chapter. 1922 was a difficult year for the couple: Alton Hampton went bankrupt, and Maud completed her petition for divorce, citing “cruel and inhuman treatment.” Maud moved into her own house, and soon after began running a successful women’s apparel business of her own. The pair had no children.

The Home (Eugene, OR), 1952⁶

Densmore was largely responsible for the creation of the Women’s Choral Club, for which she patroned with other members of the Mu Phi Epsilon music sorority, served as the first accompanist, and chaired for years to come. As the group developed artistically, Densmore cultivated the ensemble’s culture among its singers: organizing social events such as banquets and fashion shows, creating seating charts with witty epigrams for each member, collaborating with businesses to obtain sponsorships, and partnering with local organizations for the ensemble’s benefit concerts. Perhaps the most notable feature of Densmore’s legacy is the scholarship project she initiated in 1943, which remains to this day a central priority of the organization⁷.

It is difficult to overstate just how loved and appreciated Densmore was, both within the ensemble and in the larger community. Below is an excerpt from “The Home”, an independent local magazine that in 1952 published an entire issue on the Women’s Choral Club.

The Home (Eugene, OR), 1952⁸

Densmore’s community was well aware of her extraordinary accomplishments despite personal (i.e. marital) challenges. As is hinted above, the fact of her womanhood — and therefore gendered assumptions around her ability to be an effective authority figure — made Densmore all the more celebrated by those who valued women’s leadership. Thus, in exploring the impacts of Densmore’s patronage, it becomes essential to consider the feminist implications of her legacy.

It is evident that Densmore’s influence within the Women’s Choral Club went beyond merely the social structure of the group. The excerpt from The Home magazine continues⁹,

“To [Maud Densmore], an accomplished performer, music is at once a prime incentive and reward and, in sensing its universal urge, she has implanted in each of her splendid chorus something of her own philosophy and watched its flowering into into its present nobility and beauty for Eugene’s lasting memory. Surely a melodious monument to and within the life of a great leader.”

Despite her being in an administrative role, Densmore clearly made considerable contributions to the ensemble’s artistic development. Further, her guidance strengthened the interpersonal support among the members, and established avenues for professional success through scholarship funds. The significance of this type of structural support among women was illustrated by musicologist Elizabeth Wood in her 1980 book Women in Music. Wood writes¹⁰,

“Female systems of kin, friendship, and mentorship are crucial not merely for emotional interaction but for formal skill sharing and career shaping…. Courageous older, established women mentors, role models, musical mothers, effective and generous ‘patrons,’ have forced access for women to musical education, maturation, and career options.”

With this framework, it becomes distinctly evident that Densmore’s tenacious, impassioned leadership in the Women’s Choral Club held a deeper meaning: that of resisting gendered limitations on musical women by explicitly empowering their success.

Literature review: Music clubs and women’s access to the arts

In the broader historical context of the ensemble’s formative years under Maud Densmore’s guidance, several prominent and interconnecting societal challenges faced women’s access to the performing arts across the country. The most prominent constraints to groups such as the Women’s Choral Club were based on misogynist notions of women’s obligations to domestic labor, and of their capacity to be musicians with true artistic merit.

Underscoring this cultural landscape in its entirety is systemic racism, as well as racism’s intersection with misogyny to further marginalize women of color. During the era discussed in the subsequent literature (~1900–1950) many racist policies and practices were in affect in Eugene, making access to a group such as the Women’s Choral Club nearly impossible. As such, while there were significant overlaps in the experiences of white women and women of color at the time, the below discussion of the trials and triumphs relating to women’s music clubs is exceedingly (and almost exclusively) in reference to white women. Please see the Notes section for further reading on Black history at University of Oregon, Oregon’s history of racism, and the proliferation of Black clubs in America.¹¹

Eugene Women’s Choral Club rehearsing for their 1961 Winter Concert, under direction of Max Risinger ¹²

Highly influential to situating an analysis of the Women’s Choral Club is the 1997 book Cultivating Music in America : Women Patrons and Activists since 1860, edited by musicologists Ralph Locke and Cyrilla Barr. In Chapter 2, “The ‘Domestic Sphere’? Women and Music in Home,” author Linda Whitesitt discusses the growing popularity of women’s music clubs at the turn of the 20th century. She writes¹³,

“Some men (and women) worried that… involvement in “out-of-home” activities might do damage to home and family. ‘I am persuaded that there are Women’s Clubs whose objects and intents are not truly harmful, but harmful in a way that directly menaces the integrity of our homes,’ the former U.S. president Grover Cleveland was quoted as saying [in 1902]… Fortunately, such worries were not often articulated in print: even the male-dominated musical press trumpeted its praise for the work of women’s clubs.”

The political and social climate in which the Women’s Choral Club originated consequently encompassed a variety of attitudes towards women’s music clubs. After the Second World War, this discourse was at a turning point: while the previous years had drawn women into the workforce in unprecedented ways, giving many new skills and a sense of independence, the postwar era brought a societal push towards the return to female domesticity¹⁴. As such, public perception of women’s music clubs regressed as many women reentered the demanding realm of domestic labor.

Yet women choristers and directors continued to reject the assumption that women’s music clubs were frivolous, unserious pursuits — as attitudes on domesticity shifted, more women in the performing arts began advocating for updated understandings of women musicians. In a 1954 issue of Music Journal, educator Doris Paul recalls a speaker at the convention of the Michigan State Federation of Music Clubs¹⁵,

“The woman who had the floor during a forum for choral directors at [the convention] underlined every word she spoke with emotion: ‘I’m tired of hearing members of women’s choruses in the state referred to in this discussion as “just housewives.” The very inflection used indicates that some people here believe women join music groups only to get away from the grind of baby-tending, cooking, and cleaning. I grant that the girls in my chorus do find singing therapeutic, but the main reason they belong is that they experience an aesthetic pleasure from singing good music; and, as their director, I try to give it to them!’

I had to grip the arms of the chair to keep from jumping up and cheering. I thought of the members of my chorus back home. Some had been music majors in college, and but for the accident of sex that made them women, and consequently homemakers, they would be following music as a profession.”

Further in the article, Paul writes,

“It is an earnest, serious-minded, truly musical group of women, this chorus of mine… I maintain that the women who make up most choruses — mothers’ choruses connected with PTA’s, choruses affliated with women’s clubs, glee clubs made up of nurses or other professional, trade, or industrial groups — join choral organizations because they love to sing and because they enjoy music that presents a challenge. Members are not ‘mere housewives,’ ‘just mothers,’ or a ‘bunch of nurses’ who want to pass their time away singing any old thing the director and the gals happen to know.”

Paul’s article is an insightful rebuke of the dismissive, misogynistic attitudes towards women’s choirs at the time, which assumed that a group of women musicians must somehow be divorced from genuine artistry. This personal account further corroborates the conclusions made in Chapter 2 of Cultivating Music in America, in which Whitesitt writes that “women’s music clubs, by their very nature, challenged this socially accepted notion of woman’s place in the home.”¹⁶ The Women’s Choral Society is situated in this canon — from its inception, the ensemble has opposed societal limitations to their success while adapting to the changing goals of the feminist movement.

Women’s Choral Club ‘Publicity Committee’ works to plan advertising efforts for their upcoming spring concert, Eugene Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), 1956¹⁷

A stage of their own

In 1939, an anonymous author submitted an editorial to a local Eugene newspaper, excerpted below¹⁸:

“In a way our Women’s Choral Club is an expression of ‘women’s rights.” For some years these tuneful ladies have been battling against the inclination to think of them as the ‘Women’s Gleemen” or something of the sort. Just because the Gleemen are older and somewhat more famous is no sign of male monopoly on choral music. The Women’s Choral Club has its place, and its own place, in our community’s musical life.”

The author’s adamant stance is significant in underscoring the fundamental “place” of the Women’s Choral Club and sense of belonging in Eugene. They go on to write, “In their own way the women have built an organization which is different but the adequate counterpart of the Gleemen.”¹⁹ Based on the remainder of the article, it appears that the author likely was not a member of the Choral Club themself, yet they clearly maintained that the ensemble was not “lesser” because it was a women’s group. This sentiment was replicated for many years to come — throughout exploration of the archival documents held by WCS Historian Regina Claypool-Frey, a pattern arises: despite societal disenfranchisement, the ensemble continued to prove its worth in the artistic community for decades.

Early reviews of the Women’s Choral Club may read as slightly condescending, since even praise of the group was based on gendered presumptions of inferiority — as if to say, “What a surprise, women can succeed in music-making?!” For example:

“All in all the comment was, ‘Well, I didn’t know whether to hear a women’s group sing or not, but they certainly did extremely well and I enjoyed the program immensely.” — personal correspondence from Rev. George R. Turney to Maud Densmore, October 26, 1940²⁰

“[The audience] was given ear- and eye-filling proof that ensemble singing by women can be and is exciting musical experience for listener and participant alike, when a well-chosen, well-sung program is presented as was done by the Women’s Choral Club,” — G.E. Gaylord, Eugene Register-Guard, December 1945²¹

These sources offer primary insight into many contemporaneous expectations of women musicians, and further highlight how the Women’s Choral Club began to establish itself as a valued and necessary avenue for the display of women’s genuine musical talents.

•••

As the group continued to thrive into the latter half of the 20th century, there were fewer documented conversations about the implications of being an “all-women’s” group. Increasingly, the broader scholarly conversation on supporting women’s ensembles turned towards repertoire and programming. As discussed by music educators and musicologists such as Doris Paul²², Monica Hubbard²³, and Elizabeth Wood²⁴, the challenges facing directors of “all-women’s” vocal ensembles then became that of finding music of a high enough caliber for adult treble singers.

In 1970, the ensemble officially changed its name to the Women’s Choral Society²⁵. Little documentation is available on the decision to make this shift, raising questions about the impetus for this change: Did “club” have certain connotations that the women wanted to move away from? Was “society” more desirable because of its suggestions of high-status? Were there other administrative considerations?

Additional archival documents from the Women’s Choral Society do offer insight into the changing ensemble culture. For example, early programs often included explicit mentions of “Sisterhood” or shared female identity within the group. By the 1980’s this was less common, as many of the internal messages and external reviews of the group shifted to focusing predominately on their artistry and community service. However, the sentiments of WCS’s members remained poignant. In their 50th Anniversary Concert Program (1984), the Women’s Choral Society described the significance of their group²⁶:

“Since its beginning, the Women’s Choral Society has made three important contributions to the musical life of the community: music of excellent quality and great variety for its concert and outreach programs, financial aid to University of Oregon music students, and a memorable experience for each active member. Special to members of the group is the bond that singing together has created among them — bond of strength, mutual support, and joy.”

This emphasis on community-building within the ensemble suggests that the singers have maintained interpersonal priorities throughout the group’s history. Despite a slight interlude on historical materials surrounding the aforementioned themes, the Women’s Choral Society has only continued to grow in its pursuits of artistry, outreach, and community-building.

Women’s Choral Society Winter concert Program, January 20, 2019²⁷

Continuing the legacy — Advocacy and social justice in the 21st century

Over the past twenty-five years, the Women’s Choral Society has undergone several meaningful transformations. Adopting the motto “Strong in Song since 1934,” the group honors its long history while demonstrating a renewed dedication to empowering its singers. In recent years, WCS has become increasingly engaged with contemporary conversations in music education and social justice advocacy.

In 2017, the choir presented With Liberty and Justice for All, a concert commemorating the centennial of women’s suffrage. Since then, WCS has offered a series of programs that celebrate the power of collective music-making — including We Are the Voices (2019), Rise Up (2020), Let Your Light Shine (2023), Courage Hope Joy (2023), 90 Years of Song and Sisterhood (2024), and Together in Harmony (2024).²⁸

Between 2019 and 2022, the Women’s Choral Society began to reexamine its terminology and membership requirements. The group now welcomes all treble singers, and shares that they are “undergoing a ‘visioning’ process to examine our choir’s identity, mission and commitment to inclusion.”²⁹

Members of the Women’s Choral Society join in song before the start of the People’s March in Eugene, OR. Chris Pietsch / The Register-Guard (Eugene, OR), Jan. 18, 2025³⁰

On January 18, 2025, members of the Women’s Choral Society sang together at the Eugene People’s March, part of a national demonstration advocating for reproductive freedom, climate justice, access to healthcare, and LGBTQ+ rights, among other issues. This powerful interaction between music and social justice illustrates just how much our community — and, in turn, the Women’s Choral Society— has evolved in the last ninety years. While the advertisement for their very first concert in 1935 assured readers that the women were “striving not for power and volume, but rather for restraint,” the current members and leadership of the Women’s Choral Society are proud to sing with strength, conviction, and purpose.

Now directed by Dr. Melissa Brunkan, the Women’s Choral Society remains a vital part of Eugene’s musical landscape. Through annual scholarships, collaborations, and performances, the ensemble continues to uphold the commitments on which it was founded. To this extent, WCS is a living tribute to the dedicated efforts of Maud Densmore’s powerful early leadership, alongside the numerous other women who supported in the longevity of the ensemble. The Women’s Choral Society’s legacy is that of service, connection, and enduring resilience, built upon the artistic visions of generations of women; it will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role in the community for years to come.

“A song well sung is always satisfying. But when the curtain falls and the adrenaline diminishes, what sustains WCS is ‘the fellowship and the community among the women,” — Jennifer Smith³¹

•••

Notes and References

- “History.” Women’s Choral Society. Accessed November 29, 2025. https://pages.uoregon.edu/jolinda/wcs/history.html

- “Early History.” Women’s Choral Society. Accessed November 29, 2025. https://www.womenschoralsociety.org/dbpage.php?pg=history.

- “Women’s Choral Club Will Appear in First Concert.” Oregon Daily Emerald, April 16, 1935.

- From the WCS Historian archives. Digitized by author at Regina Claypool-Frey’s house, Eugene, OR. November 2025.

- “Maud Densmore.” Tree Tops. Eugene: University of Oregon, 2016. https://cpfm.uoregon.edu/sites/default/files/treetopsreport_with_landscape.pdf

- Dickson, Charles H. “Women’s Choral Club Edition.” The Home, 1952.

- “About Women’s Choral Society” Women’s Choral Society. Accessed November 29, 2025. https://www.womenschoralsociety.org/dbpage.php?pg=history.

- Dickson, Charles H. The Home

- Ibid.

- Wood, Elizabeth. “Women in Music.” Signs 6, no. 2 (1980): 283–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173927.

- The online exhibit titled “Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Rights Years — The Eugene Story” provides invaluable information about Eugene’s history of racist policies and practices. It also highlights the resistance efforts of Black individuals and groups throughout the city’s history. The exhibit was created by the Oregon Black Pioneers, in collaboration with The Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene, OR. You can view the exhibit here: https://blogs.uoregon.edu/mnchexhibits/racing-to-change/. For further reading on Black clubwomen, see this article courtesy of the Boston African American National Historic Site: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/black-women-s-club-movement.htm

- McClure. Final Rehearsals, photograph, Emerald Empire News, December 7, 1961.

- Whitesitt, Linda. “The ‘Domestic Sphere’? Women and Music in Home.” in Cultivating Music in America : Women Patrons and Activists since 1860, ed. Locke, Ralph P., and Cyrilla Barr. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft838nb58v.

- “Women and Work After World War II.” PBS. Accessed December 5, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/tupperware-work/

- Paul, Doris A. “This I Believe.” Music Journal 12 (3). Oser Communications Group, Inc., 1954

- Whitesitt, Linda. Cultivating Music in America

- Arranging Details, photograph, Register Guard, 1956

- From the WCS Historian archives. Digitized by author at Regina Claypool-Frey’s house, Eugene, OR. November 2025.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Paul, Doris A. “This I Believe.” Music Journal

- Hubbard, Monica. “Anonymous No More!” International Alliance for Women in Music Journal 2, no. 1 (1996): 12–15.

- Wood, Elizabeth. “Women in Music.” Signs

- From the WCS Historian archives. Digitized by author at Regina Claypool-Frey’s house, Eugene, OR. November 2025.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Who We Are.” Women’s Choral Society. Accessed December 6, 2025. https://www.womenschoralsociety.org/dbpage.php?pg=WhoWeAre

- Pietsch, Chris. Members of the Women’s Choral Society join in song before the start of the People’s March at Alton Baker Park in Eugene Saturday, Jan. 18, 2025. Photograph, The Register-Guard, January 18, 2025

- Cunningham, Chris. “Fellowship in Singing.” The Register Guard, September 2, 2011.